Методические указания: профессиональный английский язык для студентов 5 и 6 курсов заочного факультета специальность 060800: Экономика и управление

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ: Методические указания предназначены для студентов 5 и 6 курсов обучающихся по специальности Экономика и управление на предприятии транспорта заочного факультета. Указания составлены для организации работы студентов-заочников в межсессионный период и в период лабо-раторно-экзаменационной сессииМИНИСТЕРСТВО ТРАНСПОРТА РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ

ФГОУ ВПО

НОВОСИБИРСКАЯ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ

ВОДНОГО ТРАНСПОРТА

42 Д51

Т.А. Далецкая

МЕТОДИЧЕСКИЕ УКАЗАНИЯ: ПРОФЕССИОНАЛЬНЫЙ АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ЯЗЫК

для студентов 5 и 6 курсов заочного факультета

специальность 060800: Экономика и управление

на предприятии транспорта

Новосибирск 2007

УДК 802.0 (07) Д151

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ

![]() Рассмотрено и рекомендовано к изданию на заседании кафедры

Рассмотрено и рекомендовано к изданию на заседании кафедры

иностранных языков. Протокол №

от «19» апреля 2007г.

Рецензент: канд.фил.наук, доцент Е.И. Мартынова

Далецкая Т.А. Методические разработки: профессиональный английский язык- Новосибирск: Новосиб. гос. акад. вод. трансп., 2007. - 131с.

Данные методические указания предназначены для студентов 5 и 6 курсов обучающихся по специальности Экономика и управление на предприятии транспорта заочного факультета. Указания составлены для организации работы студентов-заочников в межсессионный период и в период лабо-раторно-экзаменационной сессии. Данные указания включают: пояснительную записку, контрольные работы № 5 и №6 разговорные темы, предусмотренные программой 5-6 курсов, и тексты для внеаудиторного чтения, а также для работы на практических занятиях

© Далецкая Т.А.,2007 © Новосибирская государственная академия водного транспорта, 2007

ЧАСТЬ 1 ПОЯСНИТЕЛЬНАЯ ЗАПИСКА............................................................... 4

ЧАСТЬ 2 Контрольное задание №5................................................................ 8

ВАРИАНТ 1 ........................................................................................................ 8

ВАРИАНТ 2...................................................................................................... 9

ВАРИАНТ 3...................................................................................................... 11

ВАРИАНТ 4.................................................................................................... 12

ВАРИАНТ 5.................................................................................................... 14

ЧАСТЬ 3 Разговорные темы............................................................................ 16

3.1 ECONOMICS........................................................................................... 16

3.2 MACROECONOMICS........................................................................... 18

3.3 MICROECONOMICS............................................................................ 20

ЧАСТЬ 4 Контрольное задание №6.............................................................. 22

ВАРИАНТ 1................................................................................................... 22

ВАРИАНТ 2.................................................................................................... 23

ВАРИАНТ 3.................................................................................................... 25

ВАРИАНТ 4.................................................................................................... 27

ВАРИАНТ 5.................................................................................................... 28

ЧАСТЬ 5 Разговорные темы............................................................................ 31

I. TRANSPORTATION ECONOMICS............................................................... 31

II. MACROECONOMICS OF TRANSPORTATION.......................................... 33

III. MICROECONOMICS OF TRANSPORTATION.......................................... 35

ЧАСТЬ 6 Тексты для чтения и перевода...................................................... 38

ЧАСТЬ 7 ПРИЛОЖЕНИЯ................................................................................. 66

ОСНОВНЫЕ ЕДИНИЦЫ ИЗМЕРЕНИЯ, ПРИНЯТЫЕ В США..................... 66

ПЛАН АННОТАЦИИ И НЕКОТОРЫЕ ВЫРАЖЕНИЯ

ДЛЯ ЕЕ НАПИСАНИЯ......................................................................... 68

ИНФИНИТИВ................................................................................................ 70

ПРИЧАСТИЕ..................................................................................................... 71

АГЛО-РУССКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ........................................................................... 73

3

![]() ЧАСТЬ

1

ПОЯСНИТЕЛЬНАЯ

ЗАПИСКА

ЧАСТЬ

1

ПОЯСНИТЕЛЬНАЯ

ЗАПИСКА

• Данные методические указания составлены для организации работы студентов-заочников НГАВТ по изучению дисциплины «профессиональный английский язык» в межсессионный период (до начала лабораторно-экзаменационной сессии) и в период лабораторно-экзаменационной сессии. Пособие адресовано студентам 5-6 курсов специальности 060800: Экономика и управление на предприятии (транспорте). Курс разработан на кафедре иностранных языков и входит в учебный план НГАВТ.

• Курс ориентирован на государственный стандарт.

• Курс направлен на самостоятельное изучение иностранного языка на базе программы средней школы.

• Курс имеет практико-ориентированный характер: для студентов проводится одна установочная лекция, на которой обсуждается учебная программа и планируется их будущая самостоятельная деятельность. В дальнейшем проводятся 10 часов занятий в период лабораторно-экзаменационной сессии, предлагаются консультации по программе обучения.

• Оценка знаний и умений студентов проводится в соответствии с целями в виде зачета на 5 курсе и экзамена на 6 курсе.

• Структура и содержание 5 курса

Курс рассчитан на 55 часов:

• Установочная лекция - 2 часа;

Практические занятия - 10 часов Самостоятельная работа - 45 часа:

1. Изучение теоретического материала - 6 часов;

2. Подготовка внеаудиторного чтения -10000 печатных знаков текстов по специальности и составление терминологического сло варя - 11 часов;

3. Изучение разговорных тем: «Экономика» - 5 часов, «Макроэкономика» - 3 часов, «Микроэкономика» - 3 часов;

4. Выполнение контрольной работы - 17 часов.

• Зачет.

• Структура и содержание 6 курса

Курс рассчитан на 55 часов:

• Установочная лекция - 2 часа;

• Практические занятия - 10 часов Самостоятельная работа - 45

часа:

1. Изучение теоретического материала - 5 часов;

2. Подготовка внеаудиторного чтения -10000 печатных знаков текстов по специальности и составление терминологического словаря - 9 часов;

3. Изучение разговорных тем: «Экономика транспорта» - 4 часов, «Макроэкономика транспорта» - 5 часов; «Микроэкономика транспорта» - 5 часов;

4. Выполнение контрольной работы -17 часов.

• Экзамен.

• Самостоятельная работа в межсессионный период

1. Студенты должны изучить следующий теоретический (грам

матический) материал:

• Глагол. Формы времени и залога. Видо-временные формы глагола действительного залога. Страдательный залог.

• Неличные формы глагола. Причастия I, II. Инфинитив.

• Простое распространенное предложение (прямой порядок слов повествовательного и побудительного предложений в утвердительной и отрицательной форме). Порядок слов вопросительного предложения.

Литература:

- Далецкая Т. А. Экономика транспорта. Новосибирск: Новосиб. гос. акад. вод. трансп., 2006

- Любой учебник грамматики английского языка

- Англо-русский и русско-английский словари.

2. Студенты должны выполнить внеаудиторное чтение (тексты

представлены в шестой части данных указаний)

Чтение и перевод текстов по специальности. Всего -10000 печатных знаков. Составление терминологического словаря. Тексты выбираются студентом самостоятельно с учетом его специализации.

3. Студенты должны выполнить контрольную работу:

Необходимо выполнить один из пяти вариантов контрольной работы №5 (для 5 курса) или № 6 (для 6 курса) из данных методических указаний. Контрольную работу необходимо выполнять в соответствии с образцами,

4

5

![]() находящимися в указанном разделе методических указаний, на основе изученного грамматического материала, который приведен в разделе 1. Вариант выбирается по последней цифре шифра студента:

находящимися в указанном разделе методических указаний, на основе изученного грамматического материала, который приведен в разделе 1. Вариант выбирается по последней цифре шифра студента:

1,2 - вариант №1 7,8 - вариант №4

3,4 - вариант №2 9,0 - вариант №5

5,6- вариант №3

Контрольную работу следует выполнять в отдельной тетради. На обложке тетради необходимо указать свою фамилию, номер контрольной работы и вариант. Контрольная работа должна выполняться аккуратным, четким почерком. При выполнении контрольной работы оставляйте в тетради широкие поля для замечаний, объяснений и методических указаний рецензента. Задания должны быть представлены в той же последовательности, в которой они даны в контрольной работе, в развернутом виде с указанием номера варианта ответа. После проверки контрольной работы её следует защитить устно. При устной защите студент должен ответить на вопросы преподавателя по материалу контрольной работы.

4. Отчетность и сроки отчетности

Результаты выполнения контрольной работы (КР) представляются в виде, указанном в пункте 3 на втором или третьем занятии.

Аудиторные занятия, аттестация. К аудиторным занятиям допускаются студенты, выполнившие домашнее задание в межсессионный период. Параллельно с прохождением аудиторных занятий студент корректирует ошибки КР, защищает КР.

На аудиторных занятиях прорабатываются разговорные темы: «Экономика», «Макроэкономика», «Микроэкономика» - на 5 курсе; «Экономика транспорта», «Макроэкономика транспорта», «Микроэкономика транспорта», которые в дальнейшем выносятся на экзамен - на 6-ом курсе. Студенты должны вести беседу с преподавателем по вышеуказанным темам. С пятою курса на экзамен выносится разговорная тема: «Экономика».

По окончании занятий на 5 курсе - сдача зачёта, на 6 курсе - экзамен.

Структура и содержание зачета за 5-ый курс

Допуск к зачету

• Чтение и перевод подготовленных текстов (10000 печатных знаков), устно - с выписанными словами;

• Устная защита контрольной работы №5.

Зачет

Письменный перевод незнакомого текста со словарем (500 печатных знаков - 30 минут);

• Беседа с преподавателем (ответы на вопросы) по одной из

пройденных тем.

Структура и содержание экзамена за 6-ой курс

Допуск к экзамену

• Чтение и перевод подготовленных текстов (10000 печатных знаков), устно - с выписанными словами;

• Устная защита контрольной работы №6.

Экзамен

• Письменный перевод незнакомого текста со словарем (500 печатных знаков - 30 минут);

• Аннотирование текста по специальности (с ограниченным применением словаря).

• Беседа с преподавателем (ответы на вопросы) по одной из пройденных тем.

6

7

![]() ЧАСТЬ 2 КОНТРОЛЬНОЕ

ЗАДАНИЕ №5

ЧАСТЬ 2 КОНТРОЛЬНОЕ

ЗАДАНИЕ №5

ВАРИАНТ 1

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите форму, функцию причастия в предложении:

• определение; часть сказуемого; обстоятельство.

1. The audience was confused.

2. One aspect of silent language frequently mentioned by researchers discussing cross-cultural differences is the varying size of the conversation bubble in each culture.

3. Knowing her pretty well, I realized something was wrong.

4. The new school is going to open next week.

5. Rejected by all his friends, he decided to become a monk.

2. Перепишите следующие словосочетания и переведите их, обращая внимание на особенности перевода на русский язык причастий

Образец : the above mentioned point - выше упомянутый пункт

A man-eating tiger, all-consuming interest, a flea-bitten dog, a self-made man, a fast-moving train.

3. Образуйте предложения со словосочетаниями из упр.2, исполь

зуя союз

that.

Образец : a much loved story - a story that is loved much.

4. Прочитайте и устно переведите текст.

1. In microeconomic theory supply and demand attempts to describe, explain, and predict the price and quantity of goods sold in competitive markets. It is one of the most fundamental economic models, used as a basic building block in a wide range of models and theories. The theory of supply and demand is crucial to explaining the market economy. It explains the mechanisms by which prices and levels of production are set.

2. Demand is the quantity of a product that a consumer or buyer would be willing and able to buy at any given price in a given period of time. Demand is

8

often represented as a table or a graph relating price and quantity demanded. Most economic models assume that consumers make rational choices. These choices are about how much to buy in order to maximize their utility - they spend their income on the products that will give them the most happiness at the least cost. The law of demand states that, price and quantity demanded are inversely related. In other words, the higher the price of a product, the less of it consumers will buy. 3. Supply is the quantity of goods that a producer or a supplier is willing to bring into the market for the purpose of sale at any given price in a given period of time. Supply is often represented as a table or a graph relating price and quantity supplied. Producers are assumed to be utility-maximizing, attempting to produce the amount of goods that will bring them the greatest possible profit. The law of supply states that, price and quantity supplied are directly proportional. In other words, the higher the price of a product, the more of it producers will create.

5. Перепишите и письменно переведите § 2,3 текста.

6. Найдите в тексте причастия, определите их форму и функцию.

7. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

ВАРИАНТ 2

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию причастия в предложении:

определение; • часть сказуемого; обстоятельство.

1. The exam results were disappointed.

2. Certain kinds of silent language that convey revealing information to other people give one particular message in one culture but a conflicting message in another culture.

3. Being unable to help her, I gave her some money.

4. Who is the man talking to Elizabeth?

5. Most of the people invited to the party didnt turn up.

2. Перепишите следующие словосочетания и переведите их, обращая внимание на особенности перевода на русский язык причастий.

Образец : the above mentioned point - выше упомянутый пункт .

9

![]()

![]() A fire-breathing dragon, a show-stopping finale, a shifty -eyed criminal, a sharp-tongued woman, a trend-setting phenomenon.

A fire-breathing dragon, a show-stopping finale, a shifty -eyed criminal, a sharp-tongued woman, a trend-setting phenomenon.

3. Образуйте предложения со словосочетаниями из упр.2, исполь

зуя союз

that.

Образец : a much loved story - a story that is loved much.

4. Прочитайте и устно переведите текст.

Marginalism

1. In marginalist economic theory, the price level is determined by the marginal cost and marginal utility. The price of all goods will be the cost of making the last one that people will purchase. The price of all the employees in a company will be the cost of hiring the last one the business needs. Marginalism looks at decisions based on the margins, what the cost to produce the next unit is, versus how much it is expected to return in profit. When the marginal return of an action reaches zero, the action stops. Marginal utility is how much more happiness or use a person receives from a purchase in contrast with buying less. Marginal rewards are often subject to diminishing returns: Less reward is obtained from more production or consumption. For example, the 1Oth bar of chocolate that a person consumes does not taste as good as the first, and so brings less marginal utility.

2. Marginalism became increasingly important in economic theory in the late 19th century, and is a tool which is used to analyze how economic systems will react. Marginal cost of production divides costs into fixed costs which must be paid regardless of how many of a commodity are produced, and variable costs. The marginal cost is the variable cost of the last unit. Marginalism states that when the profit from the next unit will be zero, that unit will not be produced. This is often termed the marginal revolution in economic thought. The marginalist theory of price level runs counter to the classical theory of price being determined by the amount of labor congealed in a commodity.

5. Перепишите и письменно переведите § 1 текста.

6. Найдите в тексте причастия, определите их форму и функцию.

7. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

ВАРИАНТ 3

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию причастия в предложении:

• определение; часть сказуемого;

• обстоятельство.

1. Most students are interested in Grammar.

2. Conversation bubble is the amount of physical distance maintained between people engaged in different kinds of conversations.

3. Not wishing to continue my studies, I decided to become a hair dresser.

4. She was crying when I saw her.

5.I found him sitting at a table covered with papers.

2. Перепишите следующие словосочетания и переведите их, обращая внимание на особенности перевода на русский язык причастий.

Образец : the above mentioned point — выше упомянутый пункт .

A death-defying stunt, a mind -boggling fact, a much-visited attraction, a well-known grammar book, a fox-hunting man.

3. Образуйте предложения со словосочетаниями из упр.2, используя

союз

that.

Образец : a much loved story - a story that is loved much.

4. Прочитайте и устно переведите текст.

Price

1. In order to measure the ebb and flow of supply and demand, a measurable value is needed. The oldest and most commonly used is price, or the going rate of exchange between buyers and sellers in a market. Price theory charts the movement of measurable quantities over time, and the relationship between price and other measurable variables. In Adam Smiths Wealth of Nations, this was the trade-off between price and convenience. A great deal of economic theory is based around prices and the theory of supply and demand. In economic theory, the most efficient form of communication comes about when changes to an economy occur through price, such as when an increase in supply leads to a lower price, or an increase in demand leads to a higher price.

10

11

2. ![]()

![]() Exchange rates are determined by the relative supply and demand of different currencies — an important issue in international trade. In many practical economic models, some form of price stickiness is incorporated to model the fact that prices do not move fluidly in many markets. Economic policy often revolves around arguments about the cause of economic friction, or price stickiness, and which is preventing the supply and demand from reaching equilibrium.

Exchange rates are determined by the relative supply and demand of different currencies — an important issue in international trade. In many practical economic models, some form of price stickiness is incorporated to model the fact that prices do not move fluidly in many markets. Economic policy often revolves around arguments about the cause of economic friction, or price stickiness, and which is preventing the supply and demand from reaching equilibrium.

3. Another area of economic controversy is about whether price measures the value of a good correctly. In mainstream market economics there are significant scarcities not factored into price. There is said to be an externalization, which is a cost or benefit to actors other than the buyer and seller, of which many examples exist, including pollution (a cost to others) and education (a benefit to others). Market economics predicts that scarce goods which are under-priced because of externalities are over-consumed. Scarce goods that are over-priced are under-consumed. This leads into public goods theory. Governments often tax and restrict the sale of goods that have negative externalities and subsidize or promote the purchase of goods that have positive externalities in an effort to correct the distortion in price caused by these externalities.

5. Перепишите и письменно переведите §1,2 текста.

6. Найдите в тексте причастия, определите их форму и функцию.

7. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

ВАРИАНТ 4

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию причастия в предложении:

• определение; часть сказуемого; обстоятельство.

1. The snack was quite satisfied.

2. Seriously depressed individuals actually have more easily compromised immune system than people who are not suffering from depression.

3. Used economically, one tin will last for six weeks.

4. This time tomorrow I will be lying on the beach.

5. Rescues are still working in the ruins of the collapsed hotel.

2. Перепишите следующие словосочетания и переведите их, обращая внимание на особенности перевода на русский язык причастий.

Образец : the above mentioned point - выше упомянутый пункт .

A weight-reducing machine, face-saving maneuver, a store-bought cake, a handmade sweater, English-speaking Canadians.

3. Образуйте предложения со словосочетаниями из упр.2, исполь

зуя союз

that

Образец : a much loved story - a story that is loved much.

4. Прочитайте и устно переведите текст.

Opportunity cost

1. Although opportunity cost can be hard to quantify, the effect of opportunity cost is universal and very real on the individual level. In fact, this principle applies to all decisions, not just economic ones. Since the work of the Austrian economist Friedrich von Wieser, opportunity cost has been seen as the foundation of the marginal theory of value.

2. Opportunity cost is one way to measure the cost of something. Rather than merely identifying and adding the costs of a project, one may also identify the next best alternative way to spend the same amount of money. The forgone profit of this next best alternative is the opportunity cost of the original choice. A common example is a farmer that chooses to farm his land rather than rent it to neighbors, wherein the opportunity cost is the forgone profit from renting. Similarly, the opportunity cost of attending university is the lost wages a student could have earned in the workforce, rather than the cost of tuition, books, and other requisite items (whose sum makes up the total cost of attendance).

3. Note that opportunity cost is not the sum of the available alternatives, but rather the benefit of the single, best alternative. Possible opportunity costs of the citys decision to build the hospital on its vacant land are the loss of the land for a sporting center, or the inability to use the land for a parking lot, or the money that could have been made from selling the land, or the loss of any of the various other possible uses—but not all of these in aggregate. One question that arises here is how to assess the benefit of dissimilar alternatives. We must determine a dollar value associated with each alternative to facilitate comparison and assess opportunity cost, which may be more or less difficult depending on the things we are trying to compare. For example, many decisions involve environmental impacts whose dollar value is difficult to assess because of scientific uncertainty. Valuing

12

13

![]()

![]() a human life or the economic impact of an Arctic oil spill involves making subjective choices with ethical implications.

a human life or the economic impact of an Arctic oil spill involves making subjective choices with ethical implications.

5. Перепишите и письменно переведите §1,2 текста.

6. Найдите в тексте причастия, определите их форму и функцию.

7. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

ВАРИАНТ 5

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию причастия в предложении:

• определение; часть сказуемого;

• обстоятельство.

1. People were depressed by the news.

2. Having failed my medical exams, I took up teaching.

3. The window was broken in the storm.

4. He came the first runner, closely followed by the second.

5. The man speaking to John (not the man dancing in the corner or the man standing by the punch) told him some shocking information.

2. Перепишите следующие словосочетания и переведите их, обращая внимание на особенности перевода на русский язык причастий.

Образец : the above mentioned point - выше упомянутый пункт .

A belt-tightening economic policy, a fast-disappearing custom, a well-trained employee, a male-dominated society, quick-growing trees.

3. Образуйте предложения со словосочетаниями из упр.2, используя союз that.

Образец : a much loved story - a story that is loved much

4. Прочитайте и устно переведите текст.

1. The theory of supply and demand usually assumes that markets are perfectly competitive. There are many buyers and sellers in the market and none of them have the capacity to significantly influence prices of goods and services. In many

real-life transactions, the assumption fails because some individual buyers or sellers or groups of buyers or sellers do have the ability to influence prices. Quite often a sophisticated analysis is required to understand the demand-supply equation of a good. However, the theory works well in simple situations.

2. Mainstream economics does not assume a priori that markets are preferable to other forms of social organization. In fact, much analysis is devoted to cases where so-called market failures lead to resource allocation that is suboptimal by some standard (highways are the classic example, profitable to all for use but not directly profitable for anyone to finance). In such cases, economists may attempt to find policies that will avoid waste directly by government control, indirectly by regulation that induces market participants to act in a manner consistent with optimal welfare, or by creating missing markets to enable efficient trading where none had previously existed. This is studied in the field of collective action. It also must be noted that optimal welfare usually takes on a Paretian norm. This norm in its mathematical application of Kaldor-Hicks method, does not stay consistent with the Utilitarian norm within the normative side of economics (which studies collective action, namely public choice). Market failure in positive economics (microeconomics) is limited in implications without mixing the belief of the economist and his or her theory.

3. The demand for various commodities by individuals is generally thought of as the outcome of a utility-maximizing process. The interpretation of this relationship between price and quantity demanded of a given good is that, given all the other goods and constraints, this set of choices is that one which makes the consumer happiest.

5. Перепишите и письменно переведите § 2 текста.

6. Найдите в тексте причастия, определите их форму и функцию.

7. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

14

15

ЧАСТЬ 3 РАЗГОВОРНЫЕ ТЕМЫ

- fields and broader categories within economics.

The core concepts of economics are value, supply, demand, price, scarcity,

marginalism.

![]() 3.1 ECONOMICS

3.1 ECONOMICS

1. Translate the following expressions into Russian:

Goods, services, to produce, limited, quantity, resources, labor, land, scarce, raw materials, de-sires, to satisfy, production, distribution, consumption, microeconomics, macroeconomics, positive economics, normative economics, economic, choice, decisions, to invest, to manufacture, to hire, to charge, to spend, to raise, tax, to borrow, value, supply, demand, price, scarcity, marginalism.

2. Read the text and translate paragraph 2,3.

1. Every society must solve three basic problems every day:

What goods and services should be produced and in what amounts? How should those goods and services be produced? • For whom should the goods and services be produced? What, how, and for whom to produce are universal problems. Human wants are practically unlimited, but all societies have only limited quantities of resources that can be used to produce goods or services. (Productive resources include labor, land, buildings, machinery, and raw materials.) If resources were not scarce, we could all have everything we ever wanted: continuous vacations, fine paintings, fast sports cars, elegant fur coats, or whatever else our dreams are made of.

2. The central economic problem is the conflict between peoples essentially

unlimited de-sires for goods and services and the limited resources that can be

used to satisfy those desires.

^ Economics is the study of how societies with limited, scarce resources decide what gets produced, how, and for whom.

3. Economics is the social science that studies the production, distribution,

and consumption of goods and services. The term economics is dated from the

publication of Adam Smiths The Wealth of Nations

in 1776. Smith referred to the

subject as political economy, but that term was replaced by economics after

1870.

Areas of economics may be divided or classified in various ways, including:

- microeconomics and macroeconomics

- positive economics (what is) and normative economics (what ought to be)

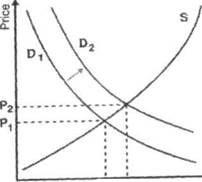

Q1 Q2 Quantity

The supply and demand model describes how prices vary as a result of a balance between product availability and demand. The graph depicts a right- shift in demand from D, to D2 along with the consequent increase in price and quantity required to reach a new equilibrium point on the supply curve (S),

3. Answer the questions:

1. What are three basic problems of the society?

2. Why are they universal?

3. What would happen if resources were not scarce?

4. What is the central economic problem?

5. What is economics?

6. When is the term economics dated?

7. How did Smith refer to the subject?

8. What are the areas of economics?

9. What are the core concepts of economics?

4. Read the text and A) think of the suitable heading, B) make up an annotation.

16

17

![]()

![]() The great nineteenth-century English economist Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) described economics as the study of mankind in the ordinary business of life. This description reflects the fact that economic choices are so common that often we do not notice that we are making them virtually every minute. You decide how best to use your scarce time. Economic choices are decisions about how to use scarce resources to satisfy peoples wants and desires. For instance, you choose between work, play, and sleep. If you choose to work, you still have to decide whether to go to class, read a textbook, or do a problem. If you choose to go shopping, you may have to decide between an expensive pair of shoes on the one hand and an inexpensive pair but a larger bank account on the other.

The great nineteenth-century English economist Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) described economics as the study of mankind in the ordinary business of life. This description reflects the fact that economic choices are so common that often we do not notice that we are making them virtually every minute. You decide how best to use your scarce time. Economic choices are decisions about how to use scarce resources to satisfy peoples wants and desires. For instance, you choose between work, play, and sleep. If you choose to work, you still have to decide whether to go to class, read a textbook, or do a problem. If you choose to go shopping, you may have to decide between an expensive pair of shoes on the one hand and an inexpensive pair but a larger bank account on the other.

Businesses and governments also make economic choices every day. A farmer must decide when and what to plant and how much to invest in new machinery. General Motors must decide which cars to manufacture, how many of each to produce, whether to invest in robots or hire more workers, whether to produce here or abroad, and how much to charge for the cars. The government must choose how much to spend on education, defense, research, and many other programs; how much to raise in taxes of various kinds; and how much to borrow. These choices all arise because resources are scarce.

3.2 MACROECONOMICS

1. Translate the following expressions into Russian:

Development, evaluation, economic policy, business strategy, national income, unemployment, inflation, investment, international trade, fluctuations, determinants, economic growth, forecasts, long-run, causes, consequences, aggregate, trends, short-run, adjustments, policy, fiscal policy, monetary policy, to succeed in, emblematic.

2. Read the text and translate paragraph 1,3.

1. Macroeconomics is a major branch of economics that deals with the performance, structure, and behavior of the economy as a whole. Macroeconomists study and seek to understand the determinants of aggregate trends in the economy with particular focus on national income, unemployment, inflation, investment, and international trade.

2. While macroeconomics is a broad field of study, there are two areas of research that are emblematic of the discipline: the attempt to understand the causes and consequences of short-run fluctuations in national income (the business cycle), and the attempt to understand the determinants of long-run economic growth

18

(increases in national income). Macroeconomic models and their forecasts are used by governments and large corporations to assist in the development and evaluation of economic policy and business strategy.

3. To avoid major economic shocks, such as great depression, governments make adjustments through policy changes. They hope that these changes will succeed in stabilizing the economy. Governments believe that the success of these adjustments is necessary to maintain stability and continue growth. This economic management is achieved through two types of strategies: Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy.

3. Answer the questions:

1. What is macroeconomics?

2. What does macroeconomics study?

3. What are the areas of research?

4. Why are macroeconomic models and their forecasts used by governments and large corporations?

5. What do governments do to avoid economic shocks?

6. How is economic management achieved?

4. Read the text and A) think of the suitable heading, B) make up an annotation.

The traditional distinction is between two different approaches to economics: Keynesian economics, focusing on demand; and supply-side (or neo-classical) economics, focusing on supply. Neither view is typically endorsed to the complete exclusion of the other, but most schools do tend clearly to emphasize one or the other as a theoretical foundation.

Keynesian economics focuses on aggregate demand to explain levels of unemployment and the business cycle. That is, business cycle fluctuations should be reduced through fiscal policy (the government spends more or less depending on the situation) and monetary policy. Early Keynesian macroeconomics was activist, calling for regular use of policy to stabilize the capitalist economy, while some Keynesians called for the use of incomes policies.

Supply-side economics delineates quite clearly the roles of monetary policy and fiscal policy. The focus for monetary policy should be purely on the price of money as determined by the supply of money and the demand for money. It advocates a monetary policy that directly targets the value of money and does not target interest rates at all. Typically the value of money is measured by reference to gold or some other reference. The focus of fiscal policy is to raise revenue for worthy government investments with a clear recognition of the impact that taxation

19

![]()

![]() has on domestic trade. It places heavy emphasis on Says law, which states that recessions do not occur because of failure in demand or lack of money.

has on domestic trade. It places heavy emphasis on Says law, which states that recessions do not occur because of failure in demand or lack of money.

3.3 MICROECONOMICS

1. Translate the following expressions into Russian:

Elasticity, game theory, uncertainty, competition, market, failure, allocation, individuals, households, to make decisions, to determine, to establish, efficient, condition, alternative use, to fail, relative price, goal, to buy, to sell, behavior, to affect, commodity, industrial organization, labor market, expenditure, workforce.

2. Read the text and translate paragraph 1, 3 .

1. Microeconomics is a branch of economics. Microeconomics studies how individuals, households, and firms make decisions to allocate limited resources, typically in markets where goods or services are being bought and sold.

2. Microeconomics examines how these decisions and behaviors affect the supply and demand for goods and services, which determines prices. It also studies how prices determine the supply and demand of goods and services. Microeconomic analysis offers a detailed treatment of individual decisions about particular commodities.

3. One of the goals of microeconomics is to analyze market mechanisms. Market mechanisms establish relative prices amongst goods, services and allocation of limited resources amongst many alternative uses. Microeconomics analyzes market failure, where markets fail to produce efficient results. It also describes the theoretical conditions needed for perfect competition. Significant fields of study in microeconomics include markets under asymmetric information, choice under uncertainty and economic applications of game theory. Also considered is the elasticity of products within the market system.

3. Answer the questions:

1. What is microeconomics?

2. What does microeconomics study?

3. What does microeconomics examine?

4. What does microeconomic analysis offer?

5. What is one of the goals of microeconomics?

6. What do market mechanisms do?

7. What do significant fields of study in microeconomics include?

4. Read the text and A) think of the suitable heading, B) make up an annotation.

Applied microeconomics includes a range of specialized areas of study, many of which draw on methods from other fields. Industrial organization and regulation examines topics such as the entry and exit of firms, innovation, role of trademarks. Law and economics applies microeconomic principles to the selection and enforcement of competing legal regimes and their relative efficiencies. Labor economics examines wages, employment, and labor market dynamics. Public finance examines the design of government tax and expenditure policies and economic effects of these policies (e.g., social insurance programs). Political economy examines the role of political institutions in determining policy outcomes. Urban economics, which examines the challenges faced by cities, such as are sprawl, air and water pollution, traffic congestion, and poverty, draws on the fields of urban geography and sociology. The field of financial economics examines topics such as the structure of optimal portfolios, the rate of return to capital, econometric analysis of security returns, and corporate financial behavior. The field of economic history examines the evolution of the economy and economic institutions, using methods and techniques from the fields of economics, history, geography, sociology, psychology, and political science.

20

21

![]()

![]() ЧАСТЬ 4 КОНТРОЛЬНОЕ ЗАДАНИЕ №6

ЧАСТЬ 4 КОНТРОЛЬНОЕ ЗАДАНИЕ №6

ВАРИАНТ 1

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию инфинитива в предложении:

• подлежащего; дополнения;

определения;

обстоятельства. Образец .I am going to start now in order not to miss the beginning. - Я собираюсь отправиться сейчас , чтобы не пропустить начало . not to miss the beginning - обстоятельство цели

1. It is easy to make mistakes.

2. Do you want to go to the lecture?

3. He got up early in order to have time to pack.

4. I need some more books to read.

5. Have you got the key to open this door?

2. Перепишите следующие предложения и переведите их, найдите и определите форму инфинитива.

Образец : I am sorry not to have come on Thursday. - Жаль, что я не пришел в четверг.

to have come -Perfect Infinitive Active.

1. Car needs to be washed.

2. I would prefer to have left yesterday, but John would prefer to leave tomorrow.

3. It is nice to be sitting here with you.

4. My sister promised to stay after party.

3. Перепишите и письменно переведите текст.

1. In the United States, airlines are run as private firms, while airports and the air traffic control network are supplied by government. Motorists and trucks operate in the private sector and travel on highways provided by the public, largely through taxes collected on motor fuels. Barges and Great Lakes carriers and oceangoing ships are private-enterprise operations, paying low levels of user fees. They travel on waterways improved and maintained by governments. Railroads

are private-enterprise ventures operating on their own roadbed and track. An exception is intercity rail passenger service, which is provided by a government agency. Oil and gas pipelines are operated by private enterprise. Mass transit operations carrying large numbers of passengers in urban areas on buses, light rail vehicles, and ferries are usually operated in the public sector.

2. At one time mass transit was provided by the private sector, but private firms could not survive much beyond World War II, when automobiles became popular. Communities, later aided by the federal government, bought out the declining private transit operators and replaced them with public-enterprise operations. Vehicles, aircraft, and ships are usually built by firms in the private sector.

4. Придумайте заголовок к тексту.

5. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

6. Прочитайте текст, придумайте заголовок, составьте аннотацию.

Научные рекомендации экономики транспорта по рационализации транспортных связей широко используются при решении таких важных народно-хозяйственных задач, как рациональное размещение производства по территории страны, выбор оптимальных размеров предприятий, экономическое обоснование специализации и кооперирования производства. Это помогает разгрузить транспорт от излишней работы, совершенствовать систему материально-технического снабжения в народном хозяйстве, более полно удовлетворять потребность в перевозках, снижать потери продукции промышленности и сельского хозяйства в процессе транспортирования. Научные разработки по совершенствованию планирования пассажирских перевозок способствуют более полному удовлетворению потребностей населения в передвижении, развитию туризма.

Вариант 2

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию инфинитива в предложении:

• подлежащего;

• дополнения;

определения; обстоятельства.

22

23

1. ![]()

![]() It made him angry to wait for people who were late.

It made him angry to wait for people who were late.

2. John decided not to go to Paris.

3. I am going to Australia to learn English.

4. Did you tell him which bus to take?

5. It was a war to end all wars.

2. Перепишите следующие предложения и переведите их, найдите и определите форму инфинитива.

Образец : I am sorry not to have come on Thursday. - Жаль, что я не пришел в четверг.

to have come - Perfect Infinitive Active.

1. I am glad to have left school.

2. He was nowhere to be seen.

3. Norman tries to get at least one stamp from every African country.

4. What do you plan to be doing when studies end?

3. Перепишите и письменно переведите текст.

Carriers set their rates between two limits. The upper limit is the value of service to the user, meaning that, if the carrier knew the true value of the service to an individual shipper or passenger that is the amount they would charge. They could not charge more than the value of service, because the customer would not use it. Carriers would like to analyze the needs of each potential user and place each in a group where the charges would equal the total value of the transportation service. Carriers cannot do this, but they do place users into groups. Airline passengers sitting in the same row on a single plane may each pay a different fare, depending on how far in advance they were willing to buy a ticket and what kind of restrictions on the use of the ticket they were willing to accept. Freight shipments also are divided into many classifications, and one factor influencing the freight rates is the value of the product, with higher-valued products paying more. Part of the rationale for this is that higher transportation costs have less impact on an expensive goods final selling price; hence they can stand to pay the higher rates. In a sense, they help subsidize the carriage of less valuable freight.

4. Придумайте заголовок к тексту

5. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

6. Прочитайте текст, придумайте заголовок, составьте аннотацию.

Транспорт - ведущая отрасль экономики, осуществляющая перевозку пассажиров и грузов. Транспорт является основой географического разделения труда и активно воздействует на размещение производства.

По характеру перевозок транспорт подразделяется на грузовой и пассажирский.

По назначению транспорт подразделяется на:

- транспорт общего пользования, обслуживающий сферу обращения товаров и население;

- транспорт необщего пользования - внутрипроизводственный, ведомственный;

- транспорт личного пользования - легковые автомобили, мотоциклы,

велосипеды, лодки, яхты и др.

По видам транспорт подразделяется на сухопутный, водный и воздушный. Особую группу составляет трубопроводный транспорт. Видом транспорта являются ленточные транспортеры, конвейеры.

Вариант 3

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию инфинитива в предложении:

подлежащего;

• дополнения;

определения;

• обстоятельства.

1. Не was the first to prove it.

2. It is difficult to understand what she is talking about.

3. I like to eat cornflakes.

4. To switch on, press red button.

5. I would like something to stop my toothache.

2. Перепишите следующие предложения и переведите их, найдите и определите форму инфинитива.

Образец : I am sorry not to have come on Thursday. - Жаль , что я не пришел в четверг .

to have come - Perfect Infinitive Active.

1. Peter offered to help Denise, but she refused to help.

2. You are to be congratulated.

24

25

3. ![]()

![]()

![]() Malcolm claims to be speaking for the entire class.

Malcolm claims to be speaking for the entire class.

4. We hope to have finished the job by next Saturday.

3. Перепишите и письменно переведите текст.

The lower limit of a transportation rate is the cost of service— the carrier should not charge less than the cost of service or it will lose money on the business. It is difficult, however, for many carriers to know or determine their costs. Railroads and pipelines have large overhead, or fixed, costs. These are costs to which the carrier is already committed without regard to the level of current business. The other form of cost is known as out-of-pocket, or variable, costs. They are related to current business. If a shipper wants to ship four railcars of freight, the railroads fixed costs—e.g., interest and taxes on its roadbed—continue without regard to whether the railroad decides to move the shippers four cars. If the railroad decides to move the cars, it incurs variable expenses, such as fuel for the engine and salary for the crew. The shipper may be willing to pay only a little more than the variable costs. The railroad will consider any payments received that are greater than its variable costs as a contribution to overhead.

4. Придумайте заголовок к тексту.

5. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

6. Прочитайте текст, придумайте заголовок, составьте аннотацию.

Водный транспорт - вид транспорта, перевозящий грузы и пассажиров по водным естественным (океаны, моря, реки, озера) и искусственным (каналы, водохранилища) путям сообщения. Водный транспорт подразделяется на морской и внутренний водный транспорт.

Внутренний водный транспорт - вид водного транспорта, производящий перевозки грузов и пассажиров по рекам, озерам и каналам речных систем (речное судоходство).

Погрузо- и пассажирообороту речной транспорт уступает автомобильному и железнодорожному транспорту. Морские перевозки - перевозки грузов и людей, осуществляемые на судах по морским коммуникациям.

Морской транспорт - вид водного транспорта, производящий перевозки грузов и пассажиров с помощью судов по океанам, морям, морским каналам (морское судоходство). Морской транспорт:

- характеризуется высокой грузоподъемностью транспортных средств, неограниченной пропускной способностью, сравнительно небольшими затратами на перевозки;

- обслуживает 4/5 всей международной торговли;

- подразделяется на каботажный и международный дальнего плавания

Вариант 4

I. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию инфинитива в предложении:

• подлежащего; дополнения; определения; обстоятельства.

1. То watch him eating really gets on my nerves.

2. She wants to dance.

3. I moved to a new flat so as to be near my work.

4. Is there anything to drink?

5. Ive got letters to write.

2. Перепишите следующие предложения и переведите их, найдите и определите форму инфинитива.

Образец : I am sorry not to have come on Thursday. - Жаль , что я не пришел в четверг .

to have come - Perfect Infinitive Active.

1. We want to be studying when he gets there.

2. I decided to go shopping, but I neglected to bring my checkbook.

3. I meant to have telephoned, but I forgot.

4. This method to be used is not new.

3. Перепишите и письменно переведите текст.

Associated with carrier costs are costs of congestion. Most people like to travel at certain hours or on certain days; the same holds for some types of freight. This phenomenon is known as peaking. Carrier costs increase during peak periods because they must provide extra equipment. Congestion itself adds to operating costs because vehicles may not be able to depart on time and must move slowly because of heavy traffic. Because of these added costs associated with congestion, many carriers charge more for operations during peak hours. The increased charges reflect two factors: the carriers higher costs and higher demand by passengers and shippers. Most users are willing to pay higher charges for service during peak

26

27

![]()

![]() periods even though they also incur additional costs in terms of waiting time. Carriers charge lower rates for off-peak periods. This reflects their lower costs and is an effort to entice users away from the peak periods. Mass transit systems often charge lower fares from 9:00 AM until 3:00 PM on weekdays, for example, encouraging shoppers to travel when a system is not filled with commuters. Carriers have incentive rates to encourage increased utilization of equipment, and they will charge less per unit of weight for larger shipments.

periods even though they also incur additional costs in terms of waiting time. Carriers charge lower rates for off-peak periods. This reflects their lower costs and is an effort to entice users away from the peak periods. Mass transit systems often charge lower fares from 9:00 AM until 3:00 PM on weekdays, for example, encouraging shoppers to travel when a system is not filled with commuters. Carriers have incentive rates to encourage increased utilization of equipment, and they will charge less per unit of weight for larger shipments.

4. Придумайте заголовок к тексту.

5. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

6. Прочитайте текст, придумайте заголовок, составьте аннотацию.

Экономика транспорта - отрасль экономической науки, изучающая закономерности развития и функционирования транспорта как особой сферы материального производства. Экономика транспорта включает экономику железнодорожного, морского, речного, автомобильного, воздушного, трубопроводного транспорта; рассматривает технико-экономические особенности каждого вида транспорта как составной части единой транспортной сети страны; изучает организацию управления, принципы и методы выбора оптимальных технических и организационных решений, экономику перевозок грузов и пассажиров, эксплуатационные работы, эффективность развития материально-технической базы, научную организацию труда и заработной платы, категории и методы измерения затрат и результатов транспортного производства. Экономика транспорта связана с такими отраслями знаний, как планирование народного хозяйства, экономика промышленности, сельского хозяйства, труда, статистика, экономическая география, с техническими науками.

Вариант 5

1. Перепишите следующие предложения, переведите их на русский язык и определите функцию инфинитива в предложении:

подлежащего; дополнения;

определения;

обстоятельства.

1. It is nice to talk to you.

2. Norman likes to collect stamps.

3. He needs a place to live in.

4. I watched him in order to know more about him.

5. It will be done in the years to come.

2. Перепишите следующие предложения и переведите их, найдите и определите форму инфинитива.

Образец : I am sorry not to have come on Thursday. - Жаль, что я не пришел в четверг.

to have come - Perfect Infinitive Active.

1. This form is to be filled in ink.

2. She was sorry to have missed Jill.

3. I noticed that he seemed to be smoking a lot.

4. Norman wasnt allowed to stay up late when he was a child.

3. Перепишите и письменно переведите текст.

Carriers are often uncertain how to determine the costs of individual hauls. An American railroad does not know how much of its overhead costs to allocate, for example, to a shipment of coal from Cheyenne, Wyo., to Duluth, Minn. Sometimes the concepts of joint products and by-products are used. A joint product is essential to the long-term survival of the firm, while a by-product is nonessential. The carrier must have a strategy to keep the joint-product types of traffic and be certain that their rates on this traffic are compensatory. Carriers also enjoy economies of scale, although this varies with mode of transportation. Railroads benefit the most. A stretch of track between two cities has the same fixed daily costs whether it handles 1 or 10,000 cars per day. Airliners have a break-even point, at a load of about 70 percent of capacity. Revenues from any passengers carried above this amount flow almost directly into the firms profits. A carrier enjoying economies of scale tries to increase volume by lowering rates to attract additional traffic. In transportation, the phrase economic density is used to describe benefits to carriers of having certain heavily used routes that are full, or dense, with traffic.

4. Придумайте заголовок к тексту

5. Письменно составьте аннотацию к тексту.

6. Прочитайте текст, придумайте заголовок, составьте аннотацию.

28

29

![]()

![]() Транспорт (от лат. transporto — переношу, перемещаю, перевожу), в общем смысле перемещение людей и грузов; одна из важнейших областей общественного материального производства. В современную транспортную систему входит транспорт общего пользования—железнодорожный транспорт, автомобильный транспорт, морской транспорт, речной транспорт,

воздушный транспорт, трубопроводный транспорт, и не общего пользования

— промышленный транспорт.

Транспорт общего пользования, доставляя продукты труда в места их потребления, продолжает производственный процесс. Грузовой транспорт хотя и не увеличивает количества продуктов, но, являясь продолжением производственного процесса, относится к материальному производству. К производственной сфере К. Маркс относит и пассажирский транспорт общего пользования. Этот вид транспорта непосредственно связан с удовлетворением потребностей людей в пространственном перемещении, как для производственных, так и личных целей. Наряду с этими видами транспорта существует транспорт личного пользования (легковые автомашины, мотоциклы, велосипеды, лодки, яхты и т.п.).

Транспорт (от лат. transporto — переношу, перемещаю, перевожу), в общем смысле перемещение людей и грузов; одна из важнейших областей общественного материального производства. В современную транспортную систему входит транспорт общего пользования—железнодорожный транспорт, автомобильный транспорт, морской транспорт, речной транспорт,

воздушный транспорт, трубопроводный транспорт, и не общего пользования

— промышленный транспорт.

Транспорт общего пользования, доставляя продукты труда в места их потребления, продолжает производственный процесс. Грузовой транспорт хотя и не увеличивает количества продуктов, но, являясь продолжением производственного процесса, относится к материальному производству. К производственной сфере К. Маркс относит и пассажирский транспорт общего пользования. Этот вид транспорта непосредственно связан с удовлетворением потребностей людей в пространственном перемещении, как для производственных, так и личных целей. Наряду с этими видами транспорта существует транспорт личного пользования (легковые автомашины, мотоциклы, велосипеды, лодки, яхты и т.п.).

ЧАСТЬ 5 РАЗГОВОРНЫЕ ТЕМЫ

I. TRANSPORTATION ECONOMICS

1 . Translate the following expressions into Russian.

Gross national product, needs, society, nation, economy, to regulate, to deregulate, to strengthen, involvement, significance, consumer, rationale, concern, mode, private, enterprise, government, facilities, passenger, freight, networks, vehicles, subfield, tolls, tax, policy, traffic, field, movement, infrastructure, triad, node, terminal, waterways, canals.

2. Read the text with a dictionary.

Transport or transportation is the movement of people and goods from one place to another. The term is derived from the Latin trans (across) and

portare (to carry).

The field of transport has several aspects: loosely they can be divided into a triad of infrastructure, vehicles, and operations. Infrastructure includes the transport networks (roads, railways, airways, waterways, canals, pipelines, etc.) that are used, as well as the nodes or terminals (such as airports, railway stations, bus stations and seaports). The vehicles generally ride on the networks, such as automobiles, bicycles, buses, trains, airplanes. The operations deal with the control of the system, such as traffic signals, air traffic control, etc, as well as policies, such as how to finance the system (for example, the use of tolls or gasoline taxes).

Broadly speaking, the design of networks is the domain of civil engineering and urban planning. The design of vehicles of mechanical engineering and specialized subfields such as nautical engineering and aerospace engineering, and the operations are usually specialized, though might appropriately belong to operations research or systems engineering.

Modes of transport

Modes are combinations of networks, vehicles, and operations, and include walking, the road transport system, rail transport, ship transport and modern aviation.

3. Answer the questions:

1. What is transportation?

2. What aspects does the field of transport have?

3. What does infrastructure include?

30

31

4. ![]() Where do the vehicles generally ride on?

Where do the vehicles generally ride on?

5. What do the operations deal with?

6. What are modes?

4. Compare transport modes in the World

Worldwide, the most widely used modes for passenger transport are the Automobile (16,000 bn passenger km), followed by Buses (7,000), Air (2,800), Railways (1,900), and Urban Rail (250).

The most widely used modes for freight transport are Sea (40,000 bn ton km), followed by Road (7,000), Railways (6,500), Oil pipelines (2,000) and Inland Navigation (1,500).

| EU 15 |

USA |

Japan |

World |

|

| GDP (PPP) per capita (€) |

19,000 |

28,600 |

22,300 |

5,500 |

| Passenger km per capita |

||||

| Private Car |

10,100 |

22,700 |

6,200 |

2,700 |

| Bus/ Coach |

1,050 |

870 |

740 |

1,200 |

| Railway |

750 |

78 |

2,900 |

320 |

S. Read the text with a dictionary.

Transportation economics is the study of the allocation of transportation resources in order to meet the needs of a society. In a macroeconomic sense, transportation activities form a portion of a nations total economic product and play a role in building or strengthening a national or regional economy and as an influence in the development of land and other resources. In a microeconomic sense, transportation involves relations between firms and individual consumers. The demand for and supply of transportation for both passengers and freight, transportation pricing, and the reasons why the transportation system is both regulated and deregulated are among its concerns. Finally, the governments involvement in each mode of transportation differs. In some instances private enterprise is used; in others, government provides the facilities and equipment, especially if the rationale for government involvement is that a strong transportation system is necessary for developing the nations economy or for its defense.

Governments involvement in transportation has both a macro- and a microeconomic significance.

6. Answer the questions:

1. What is transportation economics?

2. What does transportation involve in a macroeconomic sense?

3. What does transportation involve in a microeconomic sense?

4. What are the concerns of microeconomics?

5. Is the governments involvement in each mode of transport the same?

7. Read the text and A) think of the suitable heading, B) make up an

annotation.

Экономика транспорта как часть общей экономической системы страны определяется совокупностью заданных системных объектов, их свойств и взаимосвязей. Под совокупностью системных объектов в данном случае следует понимать вход, процесс, выход, цель, обратную связь и ограничения.

Вход экономической системы транспортной отрасли характеризуется

материально-технической базой транспортных предприятий, трудовыми ресурсами, технологическими способами перевозки и перегрузки грузов и т. п. Выход экономической системы - это удовлетворение потребностей хозяйства в перевозках грузов и пассажиров. Процесс экономической системы - осуществление перевозок грузов и пассажиров, перегрузочных работ, обслуживание транспортных и перегрузочных средств, обеспечение движения транспорта, взаимоотношения с клиентурой и т. п.

II. MACROECONOMICS OF TRANSPORTATION

1. Translate the following expressions into Russian.

To facilitate, internal, improvement, growth, development, communication, commerce, ties, to reach markets, merchandise, service, a fertile ground, inventor, innovator, entrepreneur, investor, to trade, production process, site, to sell, to exchange, perishable foods, a producer, quantity, output, economies of scale, competitive, to widen, opportunity, supplier, buyer.

2. Read the text with a dictionary.

33

32

![]()

![]() Transportations role in strengthening the economy

Transportations role in strengthening the economy

1. Transportation facilitates communication and commerce. Alexander

Hamilton, secretary of the Treasury in the 1790s, believed that internal

improvements were necessary for the nations economic growth. The word

infrastructure is used to describe all the facilities that an economy has in place,

including its transportation network of roadways, railroad tracks, and ports, as

well as the vehicles and vessels to use them. An adequate infrastructure is a

prerequisite to economic development. Transportation and communications are

important in developing and strengthening social, political, and commercial ties.

These ties must be developed before trade can be handled on a regular basis.

Transportation also is necessary for goods to reach markets where they can be

sold or exchanged for other merchandise or services. Transportation undertakings

have proved to be a fertile ground for inventors, innovators, entrepreneurs, and

their supporting investors.

2. Transportation allows each geographic area to produce whatever it does best and then to trade its product with others. It is also possible to use transportation to link together a number of different steps in the production process, each occurring at a different geographic site. Speedy modes of transportation (such as air) allow perishable foods to be distributed to wider market areas. Transportation also allows workers to reach their job sites. Lastly, because of transportation, it is possible for a producer to reach a large number of markets. This means that the quantity of output can be large enough that significant production economies of scale will result.

3. A transportation network makes markets more competitive. Economists often study resource allocation—that is, how specific goods and services are used. A transportation system improves the allocation process because it widens the number of opportunities for suppliers and buyers.

3. Answer the questions:

1. What does the word infrastructure describe?

2. Does transportation develop and strengthen social, commercial and political ties?

3. Why is it necessary?

4. What are the benefits of transportation?

5. What does transportation system do?

4. Read the text and A) think of the suitable heading, B) make up an annotation.

Gross national product (GNP) expresses a nations total economic activities, of which transportation forms a part. In the late 20th century in the United States, between 17 and 18 percent, or about one-sixth, is associated with transportation. The figure can be broken down into passenger and freight transportation. About 11 percent of GNP is accounted for by movement of people and about 6 percent by movement of freight. More than four-fifths of expenditures for movement of people in the United States are associated with the private automobile — its purchase, operation, and maintenance. About one-tenth of the expenditure on intercity travel is for travel by air; the remaining tenth is spent for rail, taxi, transit bus, and school bus. The vast majority (four-fifths) of money spent for intercity movement of freight goes to highway carriers; rails receive only about one-tenth, and the remainder is divided between air, water, and pipeline. It should be noted that more than four-fifths of the expenditures for both personal and freight intercity transportation goes to highway users. In economic terms, this represents by far the most important segment of transportation in the United States. At one time, railroads were the most important, but their role has steadily declined since World War I.

III. MICROECONOMICS OF TRANSPORTATION

1. Translate the following expressions into Russian.

Provision, capacity, load, to tend, to obscure, perspective, public, private, boundary, to include, to exclude, accounting, analysis, to supply, size, range, to provide, to carry out, safety, defense, mix, entities, profit, to support, profitable, subsidization schemes, hazardous materials, to detect, controversial, matter, to limit, length, weight, axle spacings, to own, to restrict, carrier, to capture, treaty, fare, liner, rate, to charge, route, value, shipper, carriage, an aggregate, cost.

2. Read the text with a dictionary.

1. Transport can be considered in the economic terms ofsupply

or provision

of service, and demand

or requirement for service. In engineering terms these

are capacity and load. Demand is often referred to as need which the elasticity

of price and time associated with a traffic load.

2. Transportation can be analyzed from either a public

or society

perspective, or from a private

localized set of rules. Each transport system and

activity exists from several perspectives. Generally the perspective determines

where the between what should be included and what can be excluded from an

accounting or analysis. Transportation is supplied by individual firms of all sizes

and by government agencies. The range of government involvement differs by

34

35

![]() type, or mode, of transportation and the geographic or political areas of jurisdiction. Governments are involved in providing transportation because it is necessary for economic development, for carrying out certain other functions of government (such as public safety or making it easier for individuals to reach schools or hospitals), and for national defense. So, in the supply of transportation services, a mix of public and private entities is usual. Private firms are responsive in situations where there is a profit to be made. If the market will not support profitable operators, a variety of government subsidization schemes are used.

type, or mode, of transportation and the geographic or political areas of jurisdiction. Governments are involved in providing transportation because it is necessary for economic development, for carrying out certain other functions of government (such as public safety or making it easier for individuals to reach schools or hospitals), and for national defense. So, in the supply of transportation services, a mix of public and private entities is usual. Private firms are responsive in situations where there is a profit to be made. If the market will not support profitable operators, a variety of government subsidization schemes are used.

3. In addition to economic regulation, all levels of government regulate transportation safety and movements of hazardous materials. Testing transportation operators to detect possible drug use is a controversial matter. States also limit the lengths, weights, and axle spacings of heavy trucks.

4. Economic regulation is handled differently in various other countries. A common pattern is for the government to own the railroads and airlines and to restrict other carriers if they appear to be capturing traffic from the government operations. International airline operations and services are regulated by strict treaties between the nations exchanging airline service. Actual fares are established by the International Air Transport Association (I ATA), a cartel (or organization) of all the worlds air carriers. Cartels known as conferences also regulate the by ocean liners that carry cargo on a regular basis. Each conference is made up of member lines that serve certain routes, say, between U.S. gulf ports and ports along the Baltic.

3. Answer the questions:

1. How can transport be considered?

2. What does the perspective determine?

3. How is transportation supplied?

4. Why are governments involved in providing transportation?

5. When are private firms responsive?

6. What is a cartel?

7. What do they do?

4. Read the text and A) think of the suitable heading, B) make up an annotation.

Demand for freight transportation is generally a function of demand for a product. A simple definition of demand for freight transportation is that it reflects the difference between a commoditys value in two different markets. Freight is time-sensitive. Fresh seafood is perishable; newspapers must be delivered promptly.

Shippers have money invested in inventory and often want to use faster modes of transportation to reduce the amount of time they must wait for payment

For some goods, the cost of transportation is nearly the same as the cost of the product, and it thus influences demand for both the product and its carnage. Steel-mill slag (a by-product of the steel-making process) has almost no market value and sometimes steel mills must pay to have it carried away. It can be used as an aggregate in concrete but competes with other materials, such as sand, which are very low in cost. Many recycled products also have almost no market value, and transportation costs become the major factor viewed by those who may want to buy the recycled products for some subsequent use.

36

37

![]() ЧАСТЬ 6 ТЕКСТЫ ДЛЯ ЧТЕНИЯ И ПЕРЕВОДА

ЧАСТЬ 6 ТЕКСТЫ ДЛЯ ЧТЕНИЯ И ПЕРЕВОДА

Economics

No one has ever succeeded in neatly defining the scope of economics. Economists used to say, with Alfred Marshall, the great English economist, that economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of the material requisites of wellbeing— ignoring the fact that sociologists, psychologists, and anthropologists frequently study exactly the same phenomena. Another English economist, Lionel Robbins, has more recently defined economics as the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between (given) ends and scarce means which have alternative uses. This definition — that economics is the science of economizing — captures one of the striking characteristics of the economists way of thinking but leaves out the macroeconomic approach to the subject, which is concerned with the economy as a whole.

Difficult as it may be to define economics, it is not difficult to indicate the sort of questions that economists are concerned with. Among other things, they seek to analyze the forces determining prices — not only the prices of goods and services but the prices of the resources used to produce them. This means discovering what it is that governs the way in which men, machines, and land are combined in production and that determines how buyers and sellers are brought together in a functioning market. Prices of various things must be interrelated; how does such a price system or market mechanism hang together, and what are the conditions necessary for its survival?

These are questions in what is called microeconomics, the part of economics that deals with the behaviour of such individuals as consumers, business firms, traders, and farmers. The other major branch of economics is macroeconomics, in which the focus of attention is on aggregates: the level of income in the whole economy, the volume of total employment, the flow of total investment, and so forth. Here the economist is concerned with the forces determining the income of a nation or the level of total investment; he seeks to learn why full employment is so rarely attained and what public policies should be followed to achieve higher employment or more stability.

But these still do not exhaust the range of problems that economists consider. There is also the important field of development economics, which examines the attitudes and institutions supporting economic activity as well as the process of development itself. The economist is concerned with the factors responsible for

self-sustaining economic growth and with the extent to which these factors can be manipulated by public policy.

Cutting across these three major divisions in economics are the specialized fields of public finance, money and banking, international trade, labour economics, agricultural economics, industrial organization, and others. Economists may be asked to assess the effects of governmental measures such as taxes, minimum-wage laws, rent controls, tariffs, changes in interest rates, changes in the government budget, and so on.

Economics

It is social science that seeks to analyze and describe the production, distribution, and consumption of wealth.

The major divisions of economics include microeconomics, which deals with the behaviour of individual consumers, companies, traders, and farmers; and macroeconomics, which focuses on aggregates such as the level of income in an economy, the volume of total employment, and the flow of investment. Another branch, development economics, investigates the history and changes of economic activity and organization over a period of time, as well as their relation to other activities and institutions. Within these three major divisions there are specialized areas of study that attempt to answer questions on a broad spectrum of human economic activity, including public finance, money supply and banking, international trade, labour, industrial organization, and agriculture. The areas of investigation in economics overlap with other social sciences, particularly political science, but economics is primarily concerned with relations between buyer and seller.

Construction of a system